Solarized - A Ghost Across the Hell From Me - New LP

noisey sci-fi Afrofuturism punk from the City of Brotherly Love...get on board this starship, this pushes you through a vortex to a place you need to visit.

Vocalist Alex Smith: "The frustrating part about it is continually trying to normalize marginalized people. That’s what was bothering me. I have to continually justify why I write black people, why I write queer people, why I write people with certain disabilities, why I write people who are overweight or fat or chubby, why I write interracial relationships. I have to continuously justify why I write marginalized people. It’s like, can’t black people just exist on starships? Do we have to explain why we are there to these white people who don’t understand why we’re there? It’s assumed that if there’s one black person on a starship in any speculative work, that character is only there for token reasons. But if it’s all black people on the starship, then it’s reverse racism. Somehow we’re erasing white people from this thing that they think they own. So for me, it was constantly being annoyed trying to justify our right to exist in the future. It’s basically the same as trying to justify our right to exist now. Like I was just at the UPenn bookstore and was absolutely getting profiled, and it’s kind of hard to shop looking at books and stationary when there’s this force that’s kind of zeroed in on you because you’re the only black person there at the time. So I’m just kind of sick of having to justify my existence in places. It’s not necessarily that I’m frustrated with the struggle, or the need to create things to help us get to a more liberatory moment. It’s just when we do have these moments, why do I constantly have to remind you that I’m a human being?"

I tend to think of Philadelphia punk outfit Solarized as a political band. Part of it is the gigs they play, the events they’re aligned with — the revolutionary Break Free Fest being one — and part of it is knowing vocalist and songwriter Alex Smith (who often writes about underground music for The Key) as a person, knowing the things he’s passionate about.

But Solarized is not political in the rigid, narrow sense that punk usually is — where high-octane music addresses a handful of highly specific issues in a very literal sense, offering solutions in easily-digestible, easily shout-along-able refrains. Solarized looks critically at a broad range of ideas, from racism in society to homogeneity in sci-fi (and other creative communities), from allyship that rings hollow to a speculative utopia where the marginalized people of this world have the power that’s been denied them.

On Solarized’s debut LP A Ghost Across Hell From Me, released last month on SRA Records, these topics are unpacked to the sound of hard-hitting, complex riffs and rhythms reminiscent of Drive Like Jehu, Fugazi, The Jesus Lizard, and At The Drive-In. The music hammers and swirls to Smith’s spoken-sung howls, with atmospheric film score-esque bits stitching it together, and a powerful screed shutting down the album (and all cultural gatekeepers) with ferocity.

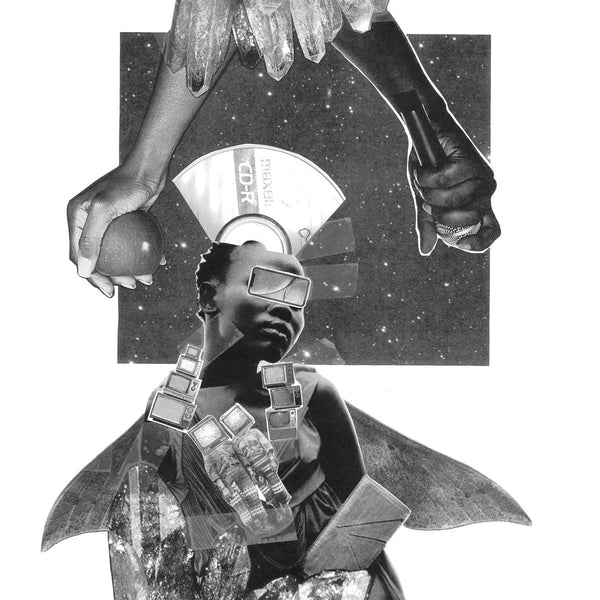

Solarized draws inspiration and strength from Afrofuturism: a movement across artistic mediums rooted in science-fiction as well as black liberation. In that vein, Smith is interdisciplinary himself: in addition to his role in the band, and as a music journalist, Smith published a collection of dystopian short stories called Arkdust this year, and is also a dazzling visual artist, whose spectral collages adorn show flyers, album covers, and most recently, gallery walls. I spoke with Smith about all of these things leading up to an art opening and Solarized gig this month.

The Key: Do you think the term “political” is the way to look at your music and your art? Or is it something different, something more?

Alex Smith: I think it’s political by default because the things that I’m talking about are not readily accessible, or appreciated by the mainstream, or even the underground. So some of the stuff I’m talking about might come across as political, or at least as challenging. To me, it’s more about praxis, and about living in a sort of, I don’t want to say lifestyle, but a sort of mentality where you want to create the world that you want to see. You want to be that creation, and not just shout against something. To me, it’s about creating the possibilities of a new world.

Like on the song “Divination,” divining something is a very powerful thing. So I draw a lot from those traditions in trying to create a new world, create a new existence for yourself, and carve out these new ways of living. Because marginalized people, people of color, queer people, have existed for so long under these sort of traps, and these systemic machinations. So it’s very important for me to sing about those things, but in a way that there’s something we can accomplish, and something we can live for, and live as.

Like you said, I’m not really trying to shout against the government or the man, in the bare bones sense of the word. But in the more spiritual, empowering sense of the word.

TK: And that seems to align with my understanding of what Afrofuturism is – creating these worlds where black and brown people, queer people, and other marginalized people have all the power that’s been stolen from them, where liberation is a reality, where we can work towards a better future that way.

AS: Those are very important aspects of Afrofuturism. And it’s kind of like what I said before, you’re using the idea of imagination and speculative sort of dreaming, and science fiction tropes, trappings, to create the world you want to see. A lot of it is about projecting Black people into the future. A lot of the work that people like Sun Ra and Anthony Braxton and Octavia Butler, a lot of what these people did, and what many people still do, is try to create the world they want to live in.

So with Afrofuturism, it’s basically black people’s interpretation of sci-fi, but through the lens of empowerment, and not sort of like how traditional science fiction uses metaphor and allegory and analogs to represent, let’s say, racism. Where aliens are the race that are discriminated against, and this is how they would attack racism and discrimination.

Whereas with Afrofuturism, we’re constantly living in it, so we kind of like embody this whole concept, not as an allegory, but as a lived way of life. Like Sun Ra was out there doing it. He created collectives, he created his own means of production, he created his own ways of manipulating the music scene to fit his speculative narrative. He wasn’t just about having it as an aesthetic, he really wanted people to come together as a collective idea, and really actually try to get to outer space. That was the ultimate goal. So I think that with a lot of Afrofuturism, there are goals to be met — not just “oh, I want to tell this cool sci-fi story,” or “oh, we want to have this rocket ship on the cover of the album.” We want to actually try to change the world.

TK: Something particularly about your work, Arkdust specifically as well as some of the lyrics on the record, it doesn’t seem as if you’re creating this total utopia for black and brown folks where there’s absolute peace and harmony. There’s definitely struggle still going on, particularly in your stories – there are a couple stories in Arkdust that seem to take place in a post-war fallout, and even the ones that don’t, it’s an alternate reality where black and brown folks are still working through the same aggressions and microagrresions they’re facing in this world. Can you talk about the importance of creating alternate worlds that, like you said, are the world you want to live in, but still have these factors that you have to work against or navigate through, challenges you’re facing.

AS: Part of it is just like, I feel like even in the utopia, white people are gonna white people. They’re still gonna be the white people of whatever group, so you’re still gonna have to constantly work on things – it’s work. It’s a constant re-imagining of everything. I was aware of this even early on, in the 90s, when it was like “oh, we need a socialist state,” “we need communism.” And I’m sittin’ here like an anarchist like “after y’all get that, I’m gonna go get my thing.” You want total freedom, but it’s a constant working towards something.

It’s also like, you don’t want to ignore the journey that got you there. To me, that’d be disrespectful to people like the Black Panthers who tried to do that, who tried to create a better world, who were very active in the community, who created testings for diseases that the quote-unquote man wasn’t worried about, like sickle cell. They created after school programs and free breakfast programs that was part of their whole praxis. So for me, just ignoring what’s happening to us now would be disingenuous, you know? Because we’re going to need to be able to tell our own story. No matter who wins, no matter what happens in the future, we need to be able to say this is what happened, this is what can happen, and who gets to tell that story.

So even though a lot of the things I write are kind of dystopic, there are elements of hope there. I would totally write a story where there’s decay and a dystopian universe, where Elon Musk and the government have finally colluded and created this sort of Gattica-esque world for us to live in. But somewhere in the basement, there’s a kid mixing unicorn blood with ancient magic, and trying to create something different and new and inspired. So part of it is that no matter how shitty things get, you can always rely on our own spirit to bring us out of it.

TK: You recently made a post on Facebook – and I’m paraphrasing – but you said “why do we need to keep imagining liberation, why do we need to keep putting ourselves in the future, why can’t liberation be now?” With the art that you create, do you often find yourself hitting that point of frustration that this is the reality that we’re in? Or is that just the frustration of living in the country we do, in the world we do?

AS: The frustrating part about it is continually trying to normalize marginalized people. That’s what was bothering me. I have to continually justify why I write black people, why I write queer people, why I write people with certain disabilities, why I write people who are overweight or fat or chubby, why I write interracial relationships. I have to continuously justify why I write marginalized people. It’s like, can’t black people just exist on starships? Do we have to explain why we are there to these white people who don’t understand why we’re there?

It’s assumed that if there’s one black person on a starship in any speculative work, that character is only there for token reasons. But if it’s all black people on the starship, then it’s reverse racism. Somehow we’re erasing white people from this thing that they think they own. So for me, it was constantly being annoyed trying to justify our right to exist in the future. It’s basically the same as trying to justify our right to exist now. Like I was just at the UPenn bookstore and was absolutely getting profiled, and it’s kind of hard to shop looking at books and stationary when there’s this force that’s kind of zeroed in on you because you’re the only black person there at the time. So I’m just kind of sick of having to justify my existence in places.

It’s not necessarily that I’m frustrated with the struggle, or the need to create things to help us get to a more liberatory moment. It’s just when we do have these moments, why do I constantly have to remind you that I’m a human being? So like, in Arkdust and onto the Solarized album, we’re just there. We are there, and if anyone tries to take that from us on those two releases, then it’s gonna be a fight. There’s gonna be a reckoning, there’s gonna be some issues. You’re either with us or against us. I’m sick of the whole allyship thing; I need accomplices and not allies, and that’s kind of what I was feeling when I wrote that post.

TK: Thinking about other artists that people think of when they talk about Afrofuturism – leaders like Sun Ra, current practitioners like Moor Mother – the way they present their music and their art, it does lean more abstract and otherworldly sonically as well as lyrically. And while your lyrics and writing is abstract, the music is very direct, I think. Why is punk your preferred vehicle for delivering the message you have?

AS: It’s not necessarily my preferred vehicle. It’s one of the many I appreciate. I don’t know that I’d say it’s my preferred; I’ve tried my hand at doing some rap stuff, I’m a house music DJ, so I’ve done various different musical genres. But even within punk, I try to mix it up a bit. On the demo, I had m. eighteen téllez come in and read a piece over Joe [Gough]’s abstract guitar stuff. We’ve had little bits and pieces here and there where it’s making punk music that’s on the weirder side. Not too much – we’re not trying to be like Dead Milkmen or Animal Collective or something – but trying to tweak it a little bit so it sounds like fresher and with a swing to it. I wouldn’t necessarily my preferred medium, but I do like the immediacy and energy of it.

TK: One of the things on the record that’s atypical of what one would hear in a punk record, on the last track, the title track, there’s the spoken word latter half that’s a callout of all these people and entities holding back marginalized voices in arts and culture. Can you talk about what writing that was like?

AS: That was actually a piece I wrote for, speaking of Moor Mother, for the Black Quantum Futurism Congos to the Carolinas volume of their anthology. And my interpretation of those anthologies is ritualistic, sigil magic. And I’m kind of into sigil magic a little bit, but I just like the idea that you can write, draw, or create something, and have that thing be a symbol to usher in what you want to see in the world. And I wrote that piece as part of a story that was basically talking about my journey from being really young and super into superheros and then having a realization that wanting to work in geek / nerd continuum was going to be kind of a struggle, there was going to be a lot of gatekeepers. So I wrote that piece talking about that, and I thought it was appropriate to put at the end of the song, because it references police brutality and racial profiling, and compares that whole system of oppression and enclosure to [comic book writer] Jack Kriby’s fourth world. I basically reference that micro-universe a lot in the song.

TK: It feels like on the one hand, obviously there’s a lot of anger and frustration that goes in to what you’re saying there. It also feels like you’re having a bit of fun with it as well. Do you feel so?

AS: Oh yeah! Totally. It’s absolutely ridiculously fun. I just like, it was my first time recording vocals in a band, and I was watching process videos of Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder, and really wanted to be loose and have some fun and write the weirdest nerdiest shit, but also angry shit too. That’s just me in a nutshell, I guess.

I never bought into the whole notion that “we’re revolutionaries and we have to be serious and we have to eat granola.” That whole stuffy idea about what a revolution should look like. To me, if you’re not injecting fun and humor and weird references that people have to look up ten years down the line, you’re not really creating art. I’m still looking at albums like Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet or It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, I still look at those albums like “I never understood that lyric until now. That sample is from where?” I love records that are constantly make me think like that. Fugazi’s In On The Kill Taker, records that are constantly making me think and challenging me but also have decent senses of humor and are also really fun.

TK: A couple songs on the album seem to nod to inspirations – “Action” references Sun Ra, who we’ve talked about. And on “Universe,” there are a few lyrics that remind me of “Olympia” by Hole — “we look the same, we talk the same.”

AS: Hmm, I don’t think so. But the story of “Universe” is ridiculous, because all of my songs have these weird origins to them. Usually conversations that I’ve had that devolve and evolve, and somehow science fiction gets thrown in. So the beginning of “Universe” is just like I’m basically being cornered at this party by this hippie white dude who’s talking my ear off about racism and about how we’re all one. That’s the first part of the song, and the second part of the song is me combatting that idea by saying that just because we are all one, doesn’t mean there’s equity. So we need to be working towards this equity, and not just hippie-wishing that it’s there. It’s just about allies who put on a false face.

TK: Performative allyship.

AS: Yeah. When everybody looks, talks, walks the same, you’re not really saying anything. “We’re all from the same space-dust, man.” You can do all the hippie arm waving you want, but ultimately, if you’re still wearing the face of the oppressor literally and figuratively, and you’re not working towards equity, what are you doing? Wake the fuck up.

TK: In “ZZZ for Vendetta,” you sing a lot about marching towards extinction. What is becoming extinct, and is its extinction a tragedy or something positive?

AS: I used that title to represent the sort of edgelord crowd who are so into V For Vendetta and Watchmen and everything that’s edgy in comics, but they sort of miss the point of them a lot of the times. So what I’m projecting to become extinct is gatekeepers and the edgelord incel gamergate [crowd], these people who like constantly shout down any representation of any marginalized people. People who have just like a normative attitude and outlook when it comes to the culture they consume. That song is basically a rallying cry for people who are non-normative, who are queer, black, neurodivergent, trans, just to be like “No. We’re taking over. We’re taking over the dance floor. We are absolutely going to be the voice of the future, and there’s nothing you can do about it, you’re headed for extinction.” That’s probably the most blunt song on the album.

We see the same attitude in music, guys who just want to argue about micro-genres and who want to like treat women like they’re coatracks. We see that same mentality in music, and it’s just constant. Let a black person try to make music that isn’t trap and try to see if we can get a decent rating on Pitchfork — it’s not gonna happen. And that whole attitude needs to be wiped out. I’m sick of it, so many of us are. We’re trying to create a scene, and this song is kind of a rallying cry sort of like “Yeah, we’re playing hardcore punk…but don’t get it twisted, bro, we are coming for you.”

TK: “Dreamcatcher” also seemed to have a lot of frustration, but this one with religion? Yes / no?

AS: No. That’s kind of about people who…I didn’t want to come off like I was dissing religion, not even dissing anything really, but trying to weed through the complications of so many different ways that people interpret the same thing. How their thing becomes the thing that traps them and they can’t see beyond it. There are a lot of cultural references in there that to some might be disparate, but to me they’re kind of the same thing. A lot of that song is inspired by my time hanging out with the Radical Faeries and experiencing a pagan culture that borrowing a lot from Asian, African, and indigenous culture, but not really in a respectful way, I thought?

TK: Not acknowledging it.

AS: Not really at all, and sort of being claiming it as their own. Sort of my odd experiences of the sort of like toxic attitudes of this deeply alternative culture was really the inspiration for that song. For me, the dreamcatcher symbolizes that. You go into these neoliberal white people’s houses and they’re some of the most racist people you’ll ever meet, and they don’t think they are but they’ll have dreamcatchers everywhere. They have ankhs and yin yang symbols but they just have the trappings of other cultures but haven’t figured out the power within their own culture, and how to use that power to help free others in other people’s liberation struggles. I really hope it doesn’t come across like I’m dissing religion, as much as I’m dissing people’s reliance on the trappings of alternative cultural things that can get us stuck in those cycles as well.

TK: “Mobius” and “Earthseed” are these Hans Zimmer-ish instrumental interludes on the album, and I really like those. How did they come to be part of the project?

AS: That’s Mental Jewelry. Steve [Montenegro] from Mental Jewelry and I have been talking about working on a project forever. And I just love what he does. He’s just an amazing sound harvester, he kind of like comes up with sounds, and he’s very good at interpreting sounds that are in other people’s minds. It was a pretty easy choice to pick him, and ask him to be part of it. Because I really thought the album needed that sort of texture. When I listen to punk albums and it’s just got “DUN-DUN-DUN-DUN-DUN”…I need sort of that break, you know? That moment where you can, maybe not breathe because there’s still tension, but you can soak in what you’re listening to. If it’s constantly pummeling, it becomes a wash, it’s not very interesting, it’s not very memorable.

So for me it’s ver important to keep these sort of bridge moments around. Soul Glo does a pretty good job of that too, and HIRS. Something to make it atmospheric and make you feel l like you’re living somewhere. Again, I’d reference the Public Enemy albums, and the 90s hardcore albums I listened to, Like Antioch Arrow and Nation of Ulysses. I always felt like I was in another world when I was listening to those records. I really wanted the record to feel immersive, and Joe and Jeff [Ziga, drummer] were all about it. They created all these strange tribal rhythms, and a lot of different shit you don’t hear on a punk record. I really wanted to do something that felt immersive and timeless and also fun and weird and that can still piss off your parents if you wanted it to.

TK: Working with Steve, did you give him an idea of the song before and after? This is our point A, this is our point C, we need the connective point B.

AS: With the pieces, I gave him a general “this is what we want. We want a few pieces that are a little more tense, we want a few pieces that have an ariness about them. And then we were like we want a few pieces that feel like Blade Runner.” We selected the ones we wanted and just mapped the songs out, they weren’t necessarily feeding out of the song before or after them, we wanted them to feel like their own pieces on the album. And of course there’s Octavia Butler’s voice on “Earthseed,” which hopefully ties everything together, because there’s a song on the album that’s exalting her in a fanboyish way. So we wanted to make things come full circle.

TK: You’re a writer , a visual artist, a musician…how much do your feel your creative pursuits stand individually and how much are they a unified body of work?

TK: It’s definitely a unified body of work. The covers are at a show called suntitled that’s’ a Black Oak house now, and will be at 40th Street Air in December, they’ll be on display as art pieces, which is totally new world for me, 2019 new. I’ve always made flyers, and I did have one art show in the 90s, but this is brand new for me. “Oh, I’m an actual artist?” Selling art is brand new, it’s kind of fun, and a little bit uncomfortable, which makes it even more fun. I have no idea what I’m doing at all in that, and that’s absolutely liberating. But there’s a connectivity there that I hope people understand, but hopefully the work can definitely stand on its on as well. If you like the Solarized record, you can bop to it as a punk record, if you like sci-fi you can check out Arkdust, it’s not like you have to buy the Arkdust book to understand the Solarized record.